Homers Hit to the Citgo Sign

When the most mundane things in life become the most meaningful...

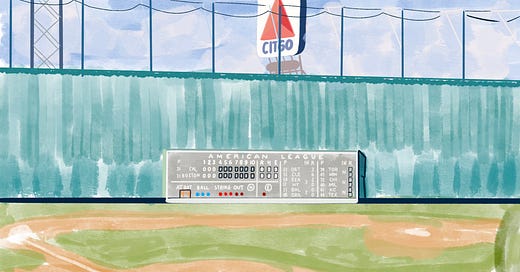

(Artwork by Terrence Doyle)

At a point where the concepts of normality and irregularity have lost all distinction, Terrence Doyle dreams of hitting homers to the Citgo sign…

I had jury duty a couple months ago at the Suffolk County Superior Court House which is located in Boston’s Government Center neighborhood, just down the hill and slightly northeast of the Massachusetts State House. I had some time to kill before checking in and dropping off my juror questionnaire, so I stopped at the Dunkin’ Donuts located at the top of Beacon Hill at the corner of Park Street and Beacon. Before entering, I scanned Boston Common from left to right, eventually fixing my gaze directly down Beacon.

As I stared out at Boston—toward Fenway and Allston and Brighton—I was surprised to catch an unimpeded view of the Citgo sign. I’ve often thought that the Citgo sign is visible from almost anywhere in Boston—it is sixty feet by sixty feet and it lights up at night, so it is hard to miss—but I’d never seen it from that vantage point. Although it was winter, my mind began to wander to hot summer days spent at Fenway Park with my family. The Citgo sign is best viewed from Fenway Park, after all, looming large above and behind the Green Monster.

The first person I remember dying was my mother’s mother, Theresa, for whom I am roughly named. I was seven and she was 59. I think I thought she was very old then but I’m now closer to her resting age than I am to the age I was when she died. She died in a hospice bed in my aunt’s house—which was next door to my own—in the fall of 1992. I remember that she was healthy, that she would bring me and my brother to this Catholic church called the Carmelite Chapel which was tucked away inside a mall in a town called Peabody, just north of Boston. We’d get ice cream in the food court and we’d pray next to Sears.

I remember that her Chrysler smelled like Marlboro lights and Canadian mints. There was a cigarette burn in the plush maroon interior bucket seat directly behind the driver’s seat; I used to pick at the hole, trying to remove the hard bits that formed along its circumference. I remember that she was healthy. And then I remember that she was not.

One of my earliest memories starts in my grandmother’s backyard on Tumelty Road in Peabody. She lived in a modest split-level, typical of and indistinguishable from the kinds of houses that sprung up in every other American suburb in the middle part of the 20th century. The grassy front lawn sloped lazily toward a sleepy street lined with dozens of the same house painted different shades of beige or yellow. Its centerpiece was a bathtub Madonna. Lush bushes and flowerbeds swaddled the foundation of the house and wrapped around to the backyard, which was chewed up by the busy feet of seven young grandchildren. Its centerpiece—at least during summers—was a kiddie pool.

It was August 26, 1989, and all of my aunts and uncles and cousins were gathered in that backyard. It might have been a combined birthday party for my older brother Sean and our oldest cousin Kelly or it might have just been a late summer cookout without an occasion. We gathered at my grandmother’s house often; we didn’t need an excuse. I remember my mother and father telling my brother and I that we had to leave early because we were going to see the Red Sox play the Detroit Tigers. I cried because I wanted to stay at Nana’s house with my cousins and my uncles and aunts and the kiddie pool, and I begged my younger cousin Carl to take my place. But neither of us were keen on going and I drew the short stick so he stayed and I threw a shit fit all the way to Fenway Park.

I remember walking through the tunnel and seeing the Green Monster for the first time. I watched Wade Boggs take batting practice, launching intentionally weak fastball after intentionally weak fastball into or over the Green Monster’s net. I could feel the crack of the bat on my skin.

I watched the outfielders warm up. Ellis Burks zipped the ball to Mike Greenwell from 200 feet and Greenwell zipped it back. The ball appeared to move along an invisible rope; it neither dipped nor rose from the moment it left a hand till the moment it settled into a glove, and my four-year-old eyes couldn’t believe what they were seeing. It all somehow looked less real in person than it did on TV. I’d forgotten the temper tantrum I threw hours before and there was suddenly no place in the world I’d rather be.

I looked out and saw a sea of people, mostly clad in red and blue. Fenway’s capacity was about 34,000 in 1989, and to me, that might as well have been every person on the planet. I wondered how many of the other kids were forced to leave cookouts at their grandmother’s house and how many of their cousins had betrayed them. I remember being envious of the hot dog vendor; how he carried the steamer on his head and a wad of cash in a sack attached to his hip. He shouted ‘hot dogs here’ in a severe Boston accent. I remember wanting to have that job someday.

I don’t remember much about the actual game. The 1989 Red Sox were an unremarkable team. They didn’t lose enough games to qualify as an embarrassment and they didn’t win enough games to qualify for the postseason. Baseball Reference tells me they were in the middle of a hot streak in late August but the pennant was already out of reach so the hot streak didn’t matter much. I remember that Roger Clemens pitched and I remember my father telling me how lucky I was to get to witness it.

Mostly, though, I remember my brother asking if anyone had ever hit a homerun off the Citgo sign. My parents both chuckled, and my father informed my brother that the Citgo sign is more than a quarter-mile from the ballpark, despite its close appearance.

“Yes, but has anyone ever hit it?”

We spent five or six days a summer in this way. We’d drive from our house in Amesbury—farther north of Boston than Peabody but equally suburban, if a bit more country—to the Oak Grove MBTA station in Malden, where we’d hop on the T and, after a switch at North Station, end up in Kenmore Square. The Citgo sign would greet us as we stepped out of the musty petrol stink of the subway and into the city air.

“What do you think, dad? Someone gonna hit it today?”

We’d walk the quarter-mile to Fenway Park, making sure to stop into the pro shop on Yawkey Way before the game so my brother and I could get new fitted hats. I was obsessed with Barry Bonds (I still am because he’s the best player in the history of the game), so I always scored a Pirates hat. My brother would eat a sausage with peppers and onions, and I—a young, boring idiot—would eat a hot dog. I don’t remember my parents eating anything.

How many games did we go to as a family? Fifty? One hundred? I can’t remember a single score and we never attended an iconic game. We weren’t there in September of 1996 when Clemens struck out twenty for the second time in his career and we weren’t there in September of 1999 when Pedro Martinez won his 23rd of the season—the highwater mark of perhaps the best pitcher there ever was. But we were at Fenway so much that it became shorthand for summer.

We never went to Disney; we didn’t have a beach house on the Cape; but we did have a family friend with Red Sox season tickets and the seats might as well have been on the field. Our seats were located in a field box on the third-base line, about 20 feet behind the visiting team’s dugout. A middle-class family could afford those seats in 1989. I’ve never been to Provence but I’ve been within sniffing distance of Jim Leyland more times than I can count.

When we did take trips, we’d travel by car and we’d stay in cheap hotels or campsites. Baseball was, of course, the motivating factor behind these rare expenditures. In the summer before my eighth-grade year, we drove to Cooperstown, NY to visit the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. In the summer after my freshman year in high school, we drove to Cleveland to go to the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame—and to a couple Indians games at Jacobs Field.

The second person I remember dying was my mother, Judy. I was 18 and she was 46. I knew she wasn’t very old then as I know she wasn’t very old now. I am now so much closer to her resting age than I am to the age I was when she died. She died on a hospice bed in our living room in the spring of 2003, weeks after I graduated from high school. She’s been gone from my life for as long as she was a part of it.

I remember that her Oldsmobile smelled like Marlboro lights and coffee. She would drive my friends and me to baseball practice and her radio would be tuned to Magic 106.7. We’d listen to Anita Baker and James Taylor and Sade and Stevie B. She’d drive us back from baseball practice and we’d play wiffle ball in the backyard. Her gardens looked like pointillist paintings if you squinted: full of tiger lilies and lilacs and hydrangeas. We would inevitably destroy one of her flowers with a line drive.

I remember she was tilling a flower bed; I remember she was smoking a cigarette and talking to her sister on the phone; I remember she was healthy and then I remember she was not.

As I sit here and write these words, I can see the Citgo sign from my kitchen window in Roxbury. It’s almost three miles away. There are three neighborhoods between it and my own; but there it is. The signage of a petrochemical company is a strange reminder of the things we miss in isolation. Lukewarm hot dogs. My mother humming along to “Sweet Love.” Her gardens. The bathtub Madonna. The kiddie pool. The crack of the bat. The ball travelling along the invisible rope.

Our father is sick now. Even if there were no pandemic and the Major League season proceeded as normal, we probably wouldn’t be able to go to Fenway as we always do sometime in early May. And because of social distancing, we can’t see each other at all.

I got to see my mother when she was sick. I got to comfort her, and she got to comfort me. It’s been more than two months since I’ve seen my father and I have no clue when I’ll get to see him next. For now, I’ll turn to memories of Fenway and baseball. I’ll send him stupid questions via text, asking him to compare players of different eras even though doing so is futile. “Pedro or Roger? Bonds or Mays? Verlander or Old Hoss Radbourn?” And I’ll send him a pixelated photograph of the Citgo sign from my window.

“Think I could hit it from here?”

You can follow Terrence Doyle on Twitter @TerrenceDoyle.

If you like this, why not subscribe to The Co-op and get our content directly into your inbox?

If you are a writer who finds themselves without a home in the wake of the pandemic, do get in touch with us. We would love to explore the idea of working with you.

Thank you for sharing - really enjoyed this. And thoughts and prayers to your Dad, Kevin whom I've known for a long, long time.

Well done Terry. A picture well-painted!